Recently, I had the pleasure of reading Anika Burgess’s latest book Flashes of Brilliance and let me just say it was such a fun dive into the early history of photography. For this issue, I have included some of my favorite sections with initial footnotes and references I made while digging into this lovely book for the first time. I hope you enjoy ~

Cumbersome precedes compactness

Introduction: Sights Unseen

I carry around a small-ish rangefinder camera with a very compact lens that can easily fit into a jacket pocket or bag. The thought of heavy gear never appealed to me and luckily in this day and age I am able to make the decision to go light and compact when it comes to my own photography gear. With the luxury/convenience that compact cameras bring us, most of us are able to endure long walks, hikes, and other excursions without having to lug around tripods, huge cameras and the accessories that were once needed to make exposures while out in the field.

“The wet collodion process dominated photography for nearly three decades…The photographer had to both expose and develop the plate while it was still wet, so there was no time to be leisurely. If the chemicals dried out, they lost their sensitivity and couldn’t create an image. From start to finish, the photographer had perhaps fifteen minutes.

This meant having all the photographic chemicals and equipment to hand. If you wanted to travel or take a landscape view, for example, you needed to carry everything with you to your chosen location–chemicals, water, portable darkroom tent, camera, tripod, developing trays, glass plates, and measuring apparatus. (And then carry them all back again.) One photographer recalled arriving at a train station on a Saturday morning in the early 1860s for a photographic outing with 120 pounds of equipment.”

After reading this section, I was instantly reminded about the California Geological Survey of the 1860s-1870s with photographer Timothy H. O'Sullivan and the Wheeler Survey during the 1870s which O’Sullivan as well as William Bell were part of. Sure, these photographers were part of a greater team of geologists, naturalists, surveyors, astronomers, botanists, etc. with mules and horses to help with most of the heavy lifting but it still puts into perspective how long and arduous those remote expeditions during the early days of photography must have been. The next time I’m out on a nice little photo walk or long hike, I’ll be trying to imagine how labor intensive it must’ve been back in the day..

Heavy gear and all.. they were still able to make stunning photographs of the landscapes they explored!

Surrealism within the world of photography

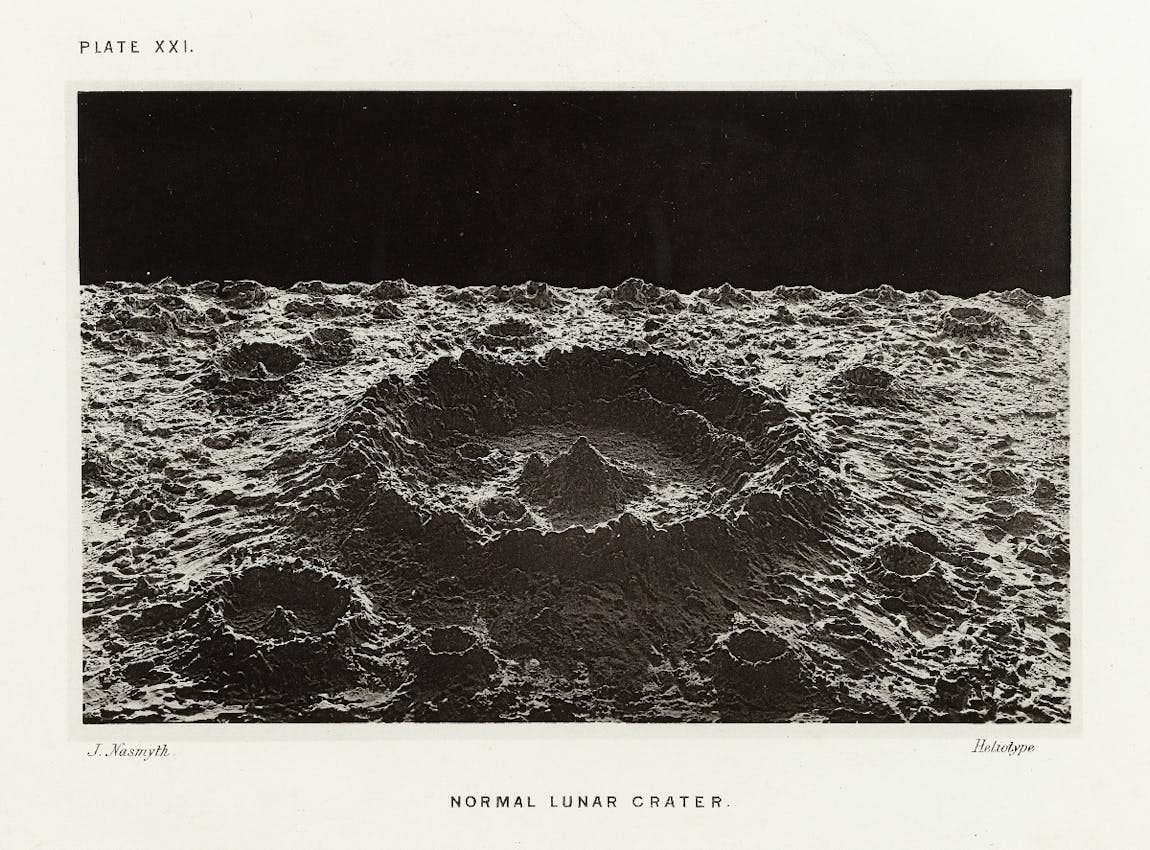

Chapter 2: To the Moon

“How the moon appears each night varies with its phases, which hemisphere you’re in, the time of night, and the weather…Even over the course of a single night, the moon’s appearance is reliable only in its inconsistency. For the nineteenth-century lunar photographer, who required stillness, this was an extremely inconvenient fact. But the moon’s allure still tempted those who relished photographic challenges and tolerated sleepless nights; of those photographers, two in particular capture the moon in ways that were innovative, imaginative, and extremely effective.”

Of the two photographers mentioned in this chapter, I was instantly intrigued by the works of James Nasmyth and his plaster sets of lunar landscapes.

“…He [Nasmyth] wasn’t deceiving his readers; he emphasized that it [his plaster model process] was “as near an approach as possible to the absolutely integrity of the original objects.” To Nasmyth, the models were the only possible way to truly depict the wonders of the lunar surface.”

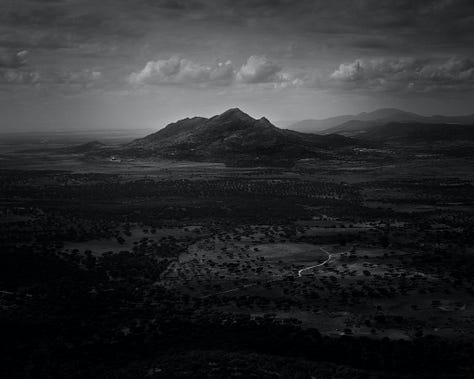

These photographs reminded me of a contemporary photographer who uses a different effect (tilt-shift lenses) to create unusual worlds/perspectives in his work that feels reminiscent of Nasmyth’s. That photographer is Rafael Trapiello and the body of work that I’m particularly thinking of is Todos los tiempos.

When the line between surrealism and photography is blurred, that’s when we get to see what a dream outside of our own minds can look and feel like..

A true bird’s-eye view

Chapter 3: Up in the Air

“Even as [Alfred] Maul was developing his highly mechanized rocket photographs, another German photographer was experimenting with aerial photographs that were far more fluid in nature…

[Julius] Neubronner was a German pharmacist who used pigeons to receive prescriptions and send out small quantities of medicine. After one of his pigeons, released in a fog, didn’t return to its dovecote for four weeks, Neubronner sought what he later described as a “photographic record of its journey.”

Neubronner designed several lightweight cameras that he attached to the pigeons with harnesses. One camera had two lenses, facing forward and backward, and produced images about 1.5 inches square.”

The tilted, wing-framed composition above is the perfect photographic representation of what a bird would see when it’s up in the air. It’s so simple yet incredibly intriguing to a “land animal” like myself. And to think that throughout the next 120 years or so (even longer if you include the earlier photographs made in hot air balloons), aerial photography would become a very important asset for war, surveying and engineering, agriculture, aid, etc. For instance, I fly drones for my surveying job on a regular basis and have never took the time to sit and think about where it all started..

A pioneer in street photography: Alice Austen

Chapter 8: Caught!

“But most crucially for the history of amateur photography, in 1888 Eastman introduced a new camera, the No. 1 Kodak…

One Kodak owner lived in Eastman’s home state, and appeared, at first glance, as the type of snap shooter who might grace Eastman’s “Kodak Girl” advertisements. She liked to travel, play tennis, and attend parties. But she owned several cameras, and photographed constantly and methodically. In so doing, she created an extraordinary valuable archive, and one that was nearly lost…

In the mid-1890s, [Alice] Austen took her bicycle and camera on the ferry from Staten Island to Manhattan and photographed street scenes that she copyrighted in an album called Street Types of New York. Just like New York street photography of today, Austen’s focus is not on architecture or infrastructure but on the people she encountered.”

In a world of endless street photographers and regurgitated videos on YouTube to go with it, it was quite exciting and refreshing to read that one of the pioneers of this genre was a female. It unfortunately does not surprise me that she is a photographer whom is quite understudied as opposed to her male counterparts. Regardless, her style and archive makes me think of how brave and badass she must’ve been to not only explore around New York in the late 1800s by herself but to do so with a camera.

Creative experimentation to scientific practicality

Chapter 12: Bones, Skin, Eyes, and Brains

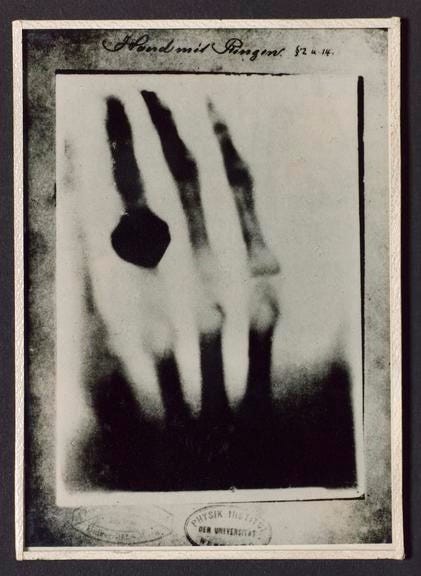

“Without a shadow of a doubt, the most astonishing, revelatory, and notorious form of photography in 1896 was the X-ray.”

After a German physicist by the name of Wilhelm Röntgen noticed a glow on a piece of paper near a Crooks tube (a partial-vacuum glass tube) that he was experimenting with, he noticed something else: when he held up vainer items between the tube and the screen to see how they were affected, he could see on the screen the bones of his own hand.

“Röntgen experimented nonstop until Christmas, trying to figure out what, exactly, he had discovered..

For this final image, taken on December 22, 1895, Röntgen’s wife Anna Bertha placed her hand on the plate, under the rays, for fifteen minutes.

The result was a shadowy and opaque view of the delicate, tapering bones inside her living human hand, punctuated, on her fourth finger, by the hovering dark mass of a ring. Röntgen, still mystified about the exact nature of his discovery, called them X-rays.”

While this new discovery opened up a world of experimental photography, it also shined light on a more practical use: “For the first time, doctors could accurately pinpoint foreign objects hidden inside the body prior to surgery. Dentists could now see the roots of teeth while they were still in the gums. Customs officers could check for smuggled goods without opening a single package.” And that was just the beginning of how X-rays could be used.

Starting with the natural and ample light that was required for the first types of photographs to now being able to make something photo-like “without a camera or visible light”, the world of photography and the geniuses involved proved very early on that photography was and is a world of boundless adventure and experimentation that is much more than a form of art; it is an ever-evolving tool to experience the world anew.

Anika Burgess is a photo editor and writer whose work has been published in the New York Times and Atlas Obscura. To read more from Flashes of Brilliance and/or the author, click here.

as always, thank you for tuning in to another issue of foto-notes ~

That was a fun and educational trip through some of the fun and very interesting things about photography. Thank you son ❤️